When brands are more trusted than media and other Trust Barometer findings

Tonia Ries,

Edelman

Paul Quigley,

NewsWhip

Topics

Earlier in the pandemic there was an initial rise in public trust but the bubble has burst. Tonia explains that the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer indicates trust in government, media, and peers has declined. This year’s central theme, information bankruptcy, underscores the gap in trust but also the opportunity for businesses, which actually experienced a rise in positive perception.

Guest

Tonia Ries is the Executive Director of Intellectual Property at Edelman, a role that includes stewardship of the Edelman Trust Barometer, the largest global survey and foremost authority on trust in institutions and brands. Now in its 21st year, the Trust Barometer surveys more than 33,000 people in 28 countries. Its cross-cultural insights are widely cited in media outlets such as The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Economist, Fortune, Forbes and others. You can follow Tonia on Twitter at @tonia_ries.

Paul Quigley: Hello everyone. I believe we are now underway. Please join me in welcoming Edelman’s Global Executive Director of IP, Tonia Ries, to the NewsWhip Pulse.

Tonia Ries: Nice to be here, thank you Paul.

Paul: Tonia has had a remarkable career in marketing, strategy, events, media, but today we want to zero in very specifically on a huge piece of IP she’s been responsible for this year, namely the Edelman Trust Barometer. And this year I personally was floored by the low levels of trust in societal institutions, particularly media, NGOs, politicians, and government that came out from the results.

And I feel like many [NewsWhip] users use our tools to understand issues and movements in society. We’ve got a whole other perspective on what’s going on with those through this very powerful research covering so many countries. So, we’re going to bring in some of the key slides and dig into the findings. So, we’re ready, Tonia, to take it away.

Tonia: Let’s go. Let’s talk data.

Paul: Let’s talk data… so let’s jump right in. There’s so much interesting stuff to talk about, and we’d invite our guests to post any questions into the channel and Danielle, our producer, will direct them my way and we’ll try and reserve some time at the end for those. So I think the first step is to put the Trust Barometer into context a little bit, Tonia. This year, it’s declaring information bankruptcy. What does that mean? Is that a break or a continuation of existing trends?

Tonia: Well, the idea behind a bankruptcy is that you get a chance to start over, right? So we’re hoping that this year’s report signals a break. As you can see from the slide, we’ve been studying trust for 21 years. And while there are some longer-term themes that we’ve been paying attention to over the years, for instance as early as 2005, we noted that shift in trust from authority figures to people like myself. That was very much a part of the rise of social media, as not just an information source, as a way of people to connect with each other.

But then that started to create shifts in, essentially, the power structure, and the hierarchy of trust. We arrived in 2018 at a very stunning finding, which is the first time that we then looked at the concerns, and rising concerns, about fake news. And at the time, two or three years ago, we really were thinking about it more in the sense of a foreign threat. The question we asked is, “how worried are you about fake news being used as a weapon against your country?” So quite aggressive. And something like three quarters of the population globally, this is a global study. This year we surveyed people in 28 countries. So there are very, very high levels of concerns.

What we’ve seen since then is a continued erosion of we don’t know who to trust. We don’t know what to believe. We don’t know where to turn for reliable information, even if we’re out there trying to sort things out on our own. Things have gotten to such a state that this is not just a foreign threat, but people even perceive it to be a domestic. That there are bad actors domestically that are deliberately sowing this information into the system. So we think it is critical to really shine a light on that, and ask all institutions to take a step back and think about how we’re going to get back to a shared sense of truth and reality.

Paul: Does declaring bankruptcy usually involve saying, “Okay, what we’ve got doesn’t work?” Is that the implication here?

Tonia: Yeah, it really is. It’s a strong word. I know it has slightly different implications in different countries and so on, but the system right now is broken. Media is the least trusted. All news sources this year have seen a steep decline. Historically, there’s been a little bit of a seesaw where there are some years that people say, “Wow, I’m much more likely to trust my neighbor down the street for information on something.” And then there’s a bit of a backlash as people see the impact of misinformation in the system, or the pollution of the information system, and then they’ve turned back to experts and authority figures. But this year trust in both experts and peers has gone down. Trust in both traditional and social media has gone down. So it’s time for a reset.

Paul: Well, let’s look at some of the metrics that are driving you towards that conclusion and that summary, Tonia. Can you describe what we’re looking at here around trust declines across all institutions?

Tonia: Sure. So this is us data. We have a global report that can see online how this plays out across the different countries. But the story in the US is pretty grim this year. You can see that in May of this year (2020) we actually went back out in the field. It was an unusual year, obviously, with the pandemic, and we wanted to see how much of an impact the onset of the pandemic had on trust in institutions. You can see what we found mid-year is a surge in trust. People needed help, knew we had a big national crisis, a global crisis, and said, “We really are going to need our institutions to step up.” And so they really turn to, you could see a big increase for government, business, for NGOs, and it was almost a cry for help.

We ended that report with a big question mark: Is this a real rise in trust, an opportunity for institutions to step up and do more? Or is it a trust bubble, essentially? And you can see across all four institutions that increased trust was followed by a decline. In the case of the media, the decline was even steeper than the rise. So big disappointments there in the fall. NGOs lost all of its increase. Government came down six, so ended the year up a little bit at the end of the year, but 42 is still a very low number.

The least amount of volatility, interestingly, was for business. The net change from January to January in the US has businesses up three or four points and is the most trusted institution in the US. That’s true globally as well, although globally, the numbers are a bit higher. The US is near the bottom of the ranking if you were to look at this data across all 28 countries.

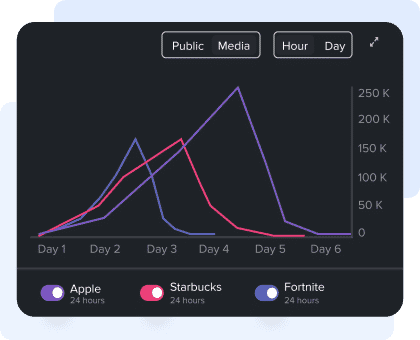

Paul: As a parallel to this, back in about May… We coordinate with the University of Michigan on something called the Iffy Quotient. This is their IP, where they use our data, which shows which stories are getting engagement and which sources, to look at are trusted sources of getting more engagement or less trusted and more partisan sources? And we saw a spike in engagement with trusted sources early in the pandemic, both on Facebook and on Twitter. And it seemed to remain the case on Facebook, but we haven’t looked at that data for the rest of the year. I kind of suspect that we may see a similar pattern, people flocked to trusted sources, and there may have been a burst in general social trust, and trusting institutions already in the pandemic, but that passed.

Tonia: I would love to see that when you have that analysis.

Paul: Great, we’ll share it. Let’s jump ahead to the business, this slide here. By the way, the full report that we’re going through can all be downloaded directly from Edelman. If you just look up the Edelman Trust Barometer, you will find all of this and plenty more. Let’s focus in on business just now as a place where there seemed to be higher trust than the other institutions. Can you explain what we’re looking at on this graph please, Tonia?

Tonia: What our research shows is that there are multiple dimensions to trust, and they can be summarized really in this graphic. Do you trust this institution or person or individual to be competent, to have the ability to get things done? And, do you trust them to do things with integrity? With a purpose and consideration, and broader considerations, than their own self-interest in a way where the benefits are fairly distributed across stakeholders? That ethical dimension is a little bit more complicated than what we’re summarizing it here, but that’s essentially what it comes down to. And even our simple trust question is, do you trust this institution or person to do what is right? So it has both the competence and the ethics implied in that question.

What we see on the chart is that, for the first time, we’ve only been doing this analysis for a couple of years now, but for the first time we see that business is now perceived as being, not just the only institution that is competent, but also is seen as ethical. Just above the line. NGOs also are seen as ethical, but they’re not seen as having the ability to get much done. Government and media are neither competent or ethical. And there’s just a massive gap there.

I think really one of the structural challenges right now is between competence for government and business. Much as we like to tell business that you have a big obligation to take on some big challenges, certainly you can’t do it alone. And we need government to get its act together in order to be a good, effective partner.

Paul: Yeah, and learn from what businesses are doing right. That would be a hard pill to swallow. I jumped past the Biden vs. Trump stuff, but I’m realizing some other things that we’re going to talk about may not make sense if we don’t spend a moment here and look at how much the trust index is different among Trump vs. Biden voters.

Tonia: We see differences and divides in the trust data in a number of different ways. And one of them, of course in the US, is this deep polarization across political divides. We fielded a survey that was a post-Trust Barometer flash poll because our main data was in the field right around the US election, so we wanted to see what was the impact of the election results on the trust findings. And so we did another quick flash poll in December about a month after the election. And this shows the change from the November original fielding, the main field date, to that December flash poll.

You can see there was a big decline, not surprisingly, among people who had voted for Trump after the election. You can just see this massive disparity. You can’t even see the trust in media among Trump voters. It literally does not exist behind that black bubble. Very little trust in government or NGOs. But here’s what I really want you to pay attention to, the one thing that both sides agree on, which is the trust in business. We keep seeing that whether it’s across the general population, across different dimensions of trust, and even among people who are feeling very disenfranchised, and not able to rely on other institutions, business is sort of this bulwark of trust.

Paul: You’ve been looking at trust for a long time, Tonia, and when you see these kinds of results, have you seen these in other societies? For example, you’ve got societies that traditionally would be called more low-trust societies, or societies with different ethnic groups where some might trust state run media less than others. Have you ever seen such a low trust count in other situations that are comparable with the split here in the level of trust that Trump voters have in media?

Tonia: I don’t know that we often see a number quite as low as that one. I really, really don’t think we have. I’d have to look hard for it.

Paul: That’s quite remarkable, because you look at many countries that have quite low levels of trust therein.

Tonia: Right now one place where there are massive trust challenges socially, for instance, is Japan. Ever since the Fukushima disaster, you could literally see, it just literally fell off the chart, whether it’s trust in government, trust in business, trust in societal leaders. That was many years ago now, and the trust levels have not recovered. So, that would be the one place that I would go look.

Paul: Right. Let’s jump down to this privileged position that employers and business find themselves in. We’ve seen that trust in employers is rising across various countries. And actually, I wanted to jump down to employer media. I believe many respondents described employer media as the most believable. Could you explain this table to us please, Tonia?

Tonia: Yeah, isn’t that remarkable? So we ask people, how often do you have to see a piece of information from each source before you’re likely to believe it? And the most readily believed source of information are “communications from my employers”, more so than well-reported media sources or information from the government, for instance. So this data point [emphasizes] the degree to which people trust employer CEOs, the degree to which they trust their employer as an institution. And again, those high levels of trust are true, even among groups that are disenfranchised in other ways, distrusting in other ways.

So, this data and this report has really gotten us into a lot of very interesting conversations with people about what it means. What is employer media? And should we perhaps think about internal communications, a little more strategically, rather than as a tactical thing? How do we put the internal communications team at the cool kids table? Include them a little bit more in the strategy, and think about how we leverage our ability to influence a workforce that in turn has influence on others. As a peer voice, they can be very trusted and very credible. But also, maybe we can broaden our definition of the workforce to think about not just people who directly work for us as a company, but what about their extended families? What about the broader community, the local community, that might think of us as a future employer or as a potential employer, as a driver of prosperity in the community?

Paul: And suppliers? I suppose your brand does it as it extends further afield. Moving right over to the other side of the graph here, Tonia, I have a personal interest in social media. Because it looks like people don’t necessarily believe something even if they see it a few times in social media. However, social media, in a sense, is a channel, right? How an employer gets the word out might be through their LinkedIn, or a Facebook Page, or Twitter, or other things. And it might be, if you follow the New York times Facebook Page, how you find that more traditional media as well. How do you think about that question? What do you think people mean when they reply that they need to see something quite a few times before they’ll trust it or might not trust it on social media?

Tonia: Yeah, and in fact, 39% said, “I will never believe it if this is the only place I see it.” And so yes, it’s quite a complicated question. I think there’s even a question from one of the attendees about this. What is it that people are really thinking about when they’re thinking about social media? And I think the truth is that most people have a higher level of awareness right now that there is a lot of misinformation on social media. That it can be very difficult to discern the real source of a piece of information. That it is easy for people to create and share information that is wrong or misleading. They might even dress it up to look like an authoritative source. So this is a real challenge for those of us who are trying to use the channel to share reliable information.

I think it’s very important for anyone in the communications field who’s using social media as a channel to think, “How do I create markers of credibility around my content?” Social is where I’m sharing and distributing the content, but is it easy for people to come back and see the source, to see how the information was put together and [the transparency]? Was this a sponsored post? Or, “What is our motive behind sharing this content?” And here’s where you could go to do more digging, and get more information if you need to see it in more places than just on Facebook to believe it.

Paul: The mere Facebook post is not the media, it’s a means of delivery and bringing people to owned channels most likely a lot of the time, right?

Tonia: Absolutely.

Paul: If we jump up to the news organizations bias slide, this is the one that really caught my attention. We worked with a great many news organizations we’re really proud to support and the work we do in the industry there. And I think as we move right to left with the statements and the percentage of the public that agree with the statements, on the right, I think is a pretty perhaps uncontroversial statement for the media sphere in 2020-2021, the media is not doing well at being objective and nonpartisan. And I don’t think that would raise an eyebrow at all, and it implies perhaps the degree of audience capture and narrative bias that a lot of publications have adopted in recent years, or maybe that was always there. But as you move across to the left, we see a statement, “journalists and reporters are purposely trying to mislead people by saying things that are false or gross exaggeration.” Is this the first year you’ve asked these questions? And can you tell us why you asked these questions?

Tonia: So yes, it’s the first year we’ve asked, so I can’t give you historical context. For those who might be journalists and reporters, just to make you feel a little bit better about that statistic on the left, we asked a similar question about government leaders and business leaders purposely trying to mislead people by saying things they know are false or are gross exaggerations. And the numbers for business and government leaders were in the same range as they are for journalists. So it’s not only journalists, there is a real suspicion of societal leaders in general. And this is what I meant when I said at the top that it’s no longer just fake news from foreign countries. We think that domestically, and this is also not just in the US, we’re seeing it around the world, that societal leaders are trying to mislead us.

There’s a real fundamental suspicion of the media when it comes to motives, and that’s what that middle data point speaks to: “Most news organizations are more concerned with supporting an ideology, or political position, then they are with informing the public.” There are other concerns that we’ve seen over the years around, “Too interested in sensational stories versus really informing us. Too interested in the click bait. Don’t have the resources to do real reporting and really bring me the facts.” But I do think that 56% is a bit of a wake-up call that we have to really think about as journalists. And for those of us who provide information, I think, again, let’s get back to making sure people understand what our motivations are, and how we are making choices about what we’re reporting on and how we’re framing those stories. It’s very important.

Paul: I think it’s fascinating to think that we’re hearkening back to the dear old days, when we were worried about sensationalism and media funding. And now we’re worrying about the majority of the public viewing media as a kind of propaganda for a particular perspective. So it’s not going the right way so far.

Tonia: Very sobering, yeah.

Paul: If we were to jump down to the information literacy slide, this is very interesting. You’ve asked people about their priorities for the year ahead. Can you tell us about these findings, Tonia?

Tonia: So one of the things we’re trying to understand right now is, along with a lot of other people, is there’ve been so many societal changes. Fall out from the pandemic, primarily, the social changes, the economic changes. So, which of those are going to be long-term and which are sort of short-term changes? And across the research, we’re seeing a big increase in the importance of “my family, my health, my personal needs”.

But then in the US, look at the other things that rise to the top. So which of these in the last year have become more important, which have become less important? We subtract the two, get a net. And aside from taking care of “my family”, it’s really about civic engagement, and engagement with information. And I think people are realizing, “Okay, if I can’t just trust what I hear from the news, or what I hear from business and government leaders, or even public health officials, I’m going to have to figure it out myself. I need to be able to sort through what is true and what is not true when it comes to the news, and even when it comes to, the science of the vaccine, for instance. Or the virus and public health measures.”

I think it’s also fascinating to me that there is a parallel rise in engagement with information, and engagement with political and civic issues… Becoming more vocal, both politically, but also in the workplace, an increase in workplace activism.

Paul: Scientific literacy is a fascinating one as well. I suppose when issues of major scientific and public health import have been so politicized as well, everyone is second-guessing many of their sources and feeling like you’ve got to go out and fend for yourself in this new environment. And probably find your new tribe of the people who will act as your filters, because it’s very hard to validate everything. There’s a related slide. People want to become more media literate. Are they doing so?

Tonia: This is the first time we looked at this, as well as part of our digging into the infodemic, as we call it. We used four criteria to determine whether we were going to say somebody had good information hygiene or good practices, personal practices, around how they consume information.

- Are they engaged in the news?

- Are they looking at diverse sources and avoiding the echo chamber?

- Are they making sure that what they read is true, checking it in multiple sources?

- And are they not amplifying or sharing information that has not been checked?

In order to say that you have good information hygiene, you had to meet three of the four criteria. We’re not even asking for an A [grade]. A C+ is good enough. And yet only 22% of Americans meet that criteria. So we have quite a ways to go. Even among those who are sharing news stories, it’s about one in four who practice three of the four of those things. So, if we’re going to take things into our own hands, or we need to, in order to have good information in the system, we have a bit of homework to do, and maybe some education.

Paul: I see a question from Kate coming through. Do you know how people who pay for news feel about news organizations, versus people who don’t? And you do an informed public split as well sometimes in your methodology?

Tonia: That’s a great question. And yes, Paul. We can’t answer it directly, Kate because we haven’t asked about, paid versus unpaid news sources. But the over sample we do for an audience we call the informed public, those are people who are college educated, they’re in the top core tile of income, and they over-index on consumption of business and public policy information. So you can assume that they’re very likely to pay for one or more news sources, to be consuming a lot of public policy or business information. They tend to have much higher levels of trust, both in institutions and in information sources.

Paul: That’s encouraging. The more we engage perhaps the more…

Tonia: Yes. It’s a little bit of a chicken and egg, right? Are they more trusting, therefore they see the value of paying for news? Or, because they get more quality content as a result of paying, they become more trusting? But it is a virtuous cycle, I think you’re right that we have to get more people into that cycle.

Paul: There may be a funny bell curve where when you just consume too much media, you end up not trusting anything at the end.

Tonia: That’s me on my worst days on my Twitter feed. Yes, absolutely.

Paul: Well, let’s jump down. There’s a lot more to the report, and I hope everyone will be coming to download it and see all the pieces that we’re going to have to skip through. But I did want to talk about what you see as some of the steps for emerging from information bankruptcy.

Tonia: Look, we’ve talked about a lot of this, so I won’t spend time on all of them. You saw at the top the higher levels of trust in business, we really think it’s important that business actively participate in the public conversation, so we’re telling CEOs, you have to get out there, you have to demonstrate leadership on issues. That really means action, before you even talk. I think it is so important, that second point, that you not only talk straight about issues, and provide reliable information and insights, but also have that empathy. Be part of the conversation because people are scared. They are nervous, they are scared, and they need their fears to be at least heard, if not addressed directly.

The commitment to trustworthy content I could talk about all day, but then also very importantly, how do we rebuild some of the fabric of society by creating partnerships? So when we tell business to lead, it doesn’t mean go do it by yourself. It means, forge those partnerships and relationships with other institutions. And maybe it’s a local government organization. Local governments are far more trusted than the federal government right now. Maybe it’s specific agencies that are working on real programs. So what are the issues that are closest to your community, your employees, your stakeholders, and how can you make meaningful action happen on those?

Paul: Brilliant. It’s nice to have some positive steps forward that we can be taking, given how challenging some of those results are. Just stopping the sharing of the report there. So that’s going to conclude for this week. As always, we zoomed through everything very quickly. I hope this has been insightful for our audience, and thanks for engaging with a whole variety of different questions coming in from different angles there, Tonia.

Before we go on we want to share that we’re launching something from NewsWhip on Monday. We’re launching a predictive intelligence newsletter. As probably most of you know, our tools predict a trajectory of all the major news stories, and in fact, all news stories each day. So we’re going to be, each morning at 10 AM Eastern sharing what are going to be the big stories in the hours ahead, and specifically, what are going to be big stories in the fields of business, healthcare and technology trends. So that’s a free service, and you can sign up directly on NewsWhip’s newsletter page.

And then we’re going to be back later in March for our next Pulse, we’re going to be joined by Bryan Pederson, the CIO at MSL. He’s going to be talking about MSL’s stack, and about the role of the informed customer journey, and how earned and influenced and owned might be eclipsing classic paid in the media mix. And I’m sure that’s something that Richard Edelman has spoken to before as well, right Tonia?

Tonia: Absolutely. One of his favorite topics.

Paul: The news pipes favor the sophisticated, the earned, and owned. So thank you so much for joining us today. It’s been a wonderful conversation, Tonia.

Tonia: Thank you. It’s been a lot of fun. And if anyone here has questions, or they want to follow up with me personally and directly, feel free to do so.

View our on-demand webinars

Sign up to our next webinar

Lessons for brands from the frontlines of social media manipulation

Governments globally, particularly in conflict zones, confront the persistent threat of social media manipulation, as evidenced by ongoing information warfare in regions like Ukraine. However, there are dedicated organizations such as Valent Projects actively working...

When distrust defines society’s relationship with government & media

Humanity’s potential for progress and creativity risks sustained damage when distrust is the foundation and society is no longer characterized by positive relationships with government, media, business, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Still, data from this...