Misinformation has long been seen as the concern of NGOs and the media, with fake news brought to the fore more than ever before under the Trump presidency, but its scope has begun to broaden even more in the last couple of years.

At NewsWhip, we’ve spent years working with organizations such as First Draft and the WHO, who are at the cutting edge of these trends. Recently, we’ve seen shifts in how those organizations think about misinformation.

Outright fake stories and fake sites (like the Denver Guardian hoax) have declined, falling victim to rigorous fact checking and platform takedowns, and the “Moldovan teenagers” can’t make easy money with fake news designed to appeal to fringe groups anymore.

And yet, misinformation persists.

Misleading facts and grey zone truths can be stitched together to create false narratives, provided underlying beliefs are strong enough. For example, those who distrust the Covid vaccines will find those rare stories of deaths or health issues post-vaccination that confirm their beliefs. These stories, as we showed in a study with NPR, were among the most shared and engaged with stories about Covid vaccines early this year, demonstrating the effect perfectly.

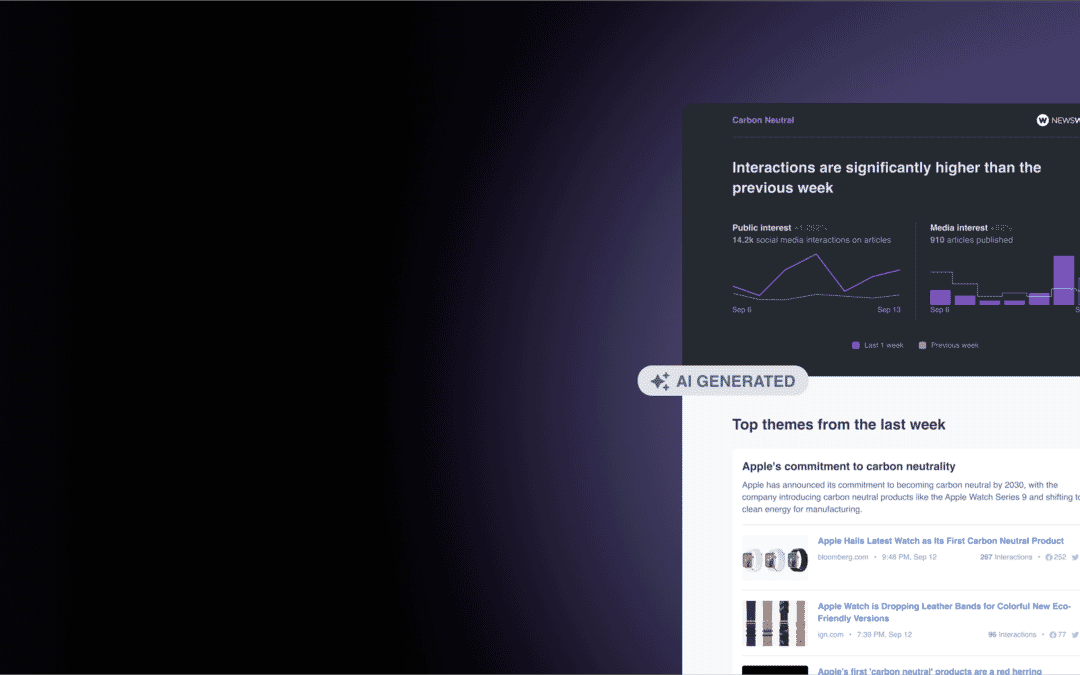

With this shift, it has become ever more important to understand how narratives are framed online, how that might affect your brands or the wider areas where you are taking a stand, and to have early alerts when narrative threats are emerging.

Based on the practices of international organizations and NGOs, we see four key areas of activity for those setting out to combat misinformation. They start with getting to know the landscape as a whole and the context in which you’re operating.

1. Survey the narrative landscape

Here, we start broad. Which groups and narratives are worth paying attention to, or encompass you and your key activities and industry? What preconceptions do people already have about you, your activities, your staff, or your business — however wrong or misleading they may be?

Organizations involved in Public Health have been at the forefront of the hard work of understanding their critics in recent years. As I’ve explored with Marshall Manson of Brunswick Group, and with AbdelHalim Abdallah of the World Health Organization, we must understand the people we disagree with if we are to change their minds, or to understand their influence.

Some of these groups may have completely false beliefs about your organization. Others will have taken some facts or statements and twisted them into something you barely recognize, as part of a wider narrative. So it goes. You must still take the time to understand them, at least to avoid surprises.

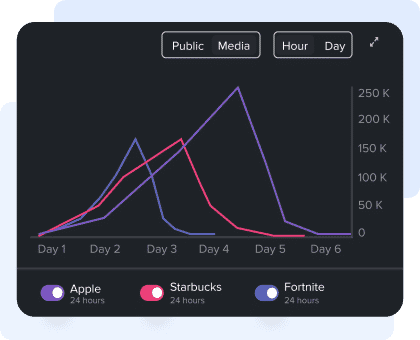

These groups, factions, or narratives can be researched through analyzing viral narratives (the stories being shared), looking at where these spread (social accounts), and then discerning wider stories and beliefs. Once mapped and maintained, a monitoring framework can prevent future surprises.

This kind of narrative survey can form part of a wider monitoring framework. For example, Samsung’s communications team has built a data-informed reputation risk monitoring framework around the top areas the company cares about reputationally, identifying key narratives, influencers and outlets. Detractors and critics are part of your reputation landscape too.

2. Detect and quantify misinformation fast

In our work supporting anti-misinformation efforts around elections since 2017, NGOs have found that speedy intervention is key when a story is blowing up, while staying quiet is the right move if it’s not. As Sam Dubberly, who headed up Cross Check for the last French Presidential elections puts it: “We always had this tension between ‘putting fuel on the fire’ or the question of ‘are we too late,’ and the story has travelled halfway around the world already. That was really where Spike came into its own.”

This same agile philosophy is being adopted by brands too. Jeff Olson of Rite Aid says that “when a disinformation situation is upon us, the first thing I try to do is look at where the data is. What is analytics saying? Are certain conversations elevating in social? How fast is this moving? Is it sticking to a geography?”

Some stories might be false, but might also be failing to spread. Here, the best response is often no response, as I explored in a previous description of predictive crisis management. Staying away from engagement with activists, outlets or others who are pushing a misleading narrative or astroturfing a scandal avoids adding to the story.

Real-time data can be tremendously helpful in these situations. It can show when the reach of a story is limited to a particular group or echo chamber. Here, stepping in might become the communications equivalent of wrestling with a pig.

Our friends at Brunswick Group use a ‘forest fire’ analogy. In fighting a forest fire, sometimes you need to dig trenches, create gaps, and isolate the fire to a particular place. And then you let it burn.

3. Use data for your planning

When taking action against a piece of misinformation that starts to spread, we recommend careful, predictive planning. That means using the channels that are likely to reach the people you want to inoculate against a particular piece of misinformation, or misinformed narrative.

These can mean building credibility yourself and also linking with journalists or publishers who get significant engagement on the relevant topic, or who have shot to relevancy recently.

Marshall Manson of Brunswick Group talks about the importance of building community and having trusted spokespeople. “We know that there’s a relationship between how someone communicates and being part of a community. If you are seen as part of a community, you’re more likely to be trusted and believed. So that’s the value of third-party spokespeople.”

Some PR agencies have sharpened this granular, data-informed approach to planning to a fine point. In the case of a regional or local focus, using data to understand local narratives will enable you to frame the story so it ‘lands’, as Todd Ringler of Edelman describes:

“We had one client that was embarking on an experiential type of program that they wanted to do in multiple markets – 12 cities nationally…

“We used NewsWhip to go in and audit how this topic was being discussed in various cities’ media…. Once we were able to go into each city and come back with insights for how this particular community spoke, how the media spoke about it, which topics rose to the fore around this topic, we were able to go back to the client and say, “Now that we’ve looked at the various cities, we can tell you that this is not going to land well in about 80% of the cities that you want to go into. And we need to dial the program in different directions, depending if we’re going into Miami or Atlanta or Philadelphia or Dallas.”

4. Bring back facts – and use your own channels for them

In this kaleidoscope of narratives, is there any role for good old fashioned “truth”? Perhaps so. In the most recent Edelman Trust barometer, the private sector is more trusted than media, government or NGOs by a majority of Americans. I suspect this is at least partly down to the idea that public companies are committed to telling the truth, at least on a financial level, to their shareholders, customers and stakeholders, and are accountable to market forces.

Here, perhaps, the private sector may have a trust advantage when compared with NGOs, media and other institutions.

Given this trust advantage, companies should invest in continuous engagement through owned channels to make sure their story can get out, as clearly as it can.

This is an idea reinforced by Amil Khan of Valent Projects, who spoke to us about the advantage of having a voice when attacked by disinformation:

It’s much easier [for bad actors] to target an organization that will not put out a lot of information, that is kind of quiet and wants to hold everything back. Because you can target them, and you can know that they’re not going to respond for a week or two weeks. …Whereas if a more nimble organization has already built and is constantly refining and pushing out this idea: “This is what we are. This is what we do. And if we mess up, we’ll own it, and we’ll try and rectify it.”

So an organization with trusted relationships — and active, owned channels to reach its audience — is simply more resistant to a disinformation attack.

“There’s so much opinion masquerading as fact now,” says Ilana Finley, of Converse. “As a brand covered by the media, one of the things we are increasingly doing is driving more of our own news. We have the platforms to do so. It’s critical for us to have all of the fact-based information there about what we’re doing as a company.”

The actions I’ve listed above to take preventative action against misinformation seem like a tall order: Mapping the narrative landscape, monitoring it in real time, using data to inform planning, partnerships and decisions, and building owned channels. However, the same actions will serve a wider purpose: they’re exactly what brands need to do to build and maintain a story today.

If you’d like to see how our tools can help in the fight against misinformation, get in touch here.