We recently sat down with Sarah Brandt, Executive Vice President of Partnerships for NewsGuard, and Dr. Paul Resnick, the Michael D. Cohen Collegiate Professor of Information and Associate Dean for Research and Faculty Affairs of the University of Michigan School of Information, to discuss misinformation and current trends regarding the topic.

In this digital age, people have become increasingly aware of misinformation, to the point that it’s moving beyond its traditional interested audiences. A topic saturated by fact checkers, journalists, and NGOs has moved toward an ever broader demographic. Covid-19 and the United States’ current political landscape have made misinformation all the more relevant, so it’s necessary to understand how its role in the media influences the public.

To start with a working definition of the term, Brandt describes misinformation as any information that’s false, misleading, deceptive, or causing harm. “There’s a lot of range of falsehoods and categories of falsehoods that can fall into this bucket of misinformation,” says Brandt. “With NewsGuard, what we do is focus on the clearly and egregiously false information.”

Dr. Resnick added that it’s very important to include the term “misleading” when it comes to misinformation. Things might not be outright false, but they deliberately, or inadvertently, invite the reader or viewer to be misinformed at the end.

Measuring misinformation and using NewsWhip

Both NewsGuard and the University of Michigan have their own unique ways of measuring misinformation. We talked about their processes and how misinformation is rated in their respective fields.

NewsGuard was formed by a team of journalists, with the main function of rating the reliability of news sources. The process is completely human driven — they use reporting and journalistic criteria, but rather than evaluating individual articles or debunking individual claims, they provide reliability ratings for the news source as a whole.

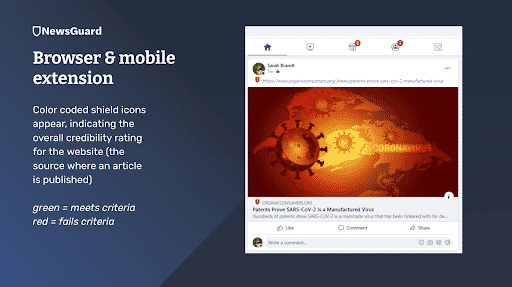

“What we do is use nine criteria to rate each website, and based on how the websites fare on the criteria that it received, they receive an overall green rating indicating that they’re generally reliable, or an overall red rating indicating they’re generally unreliable,” says Brandt.

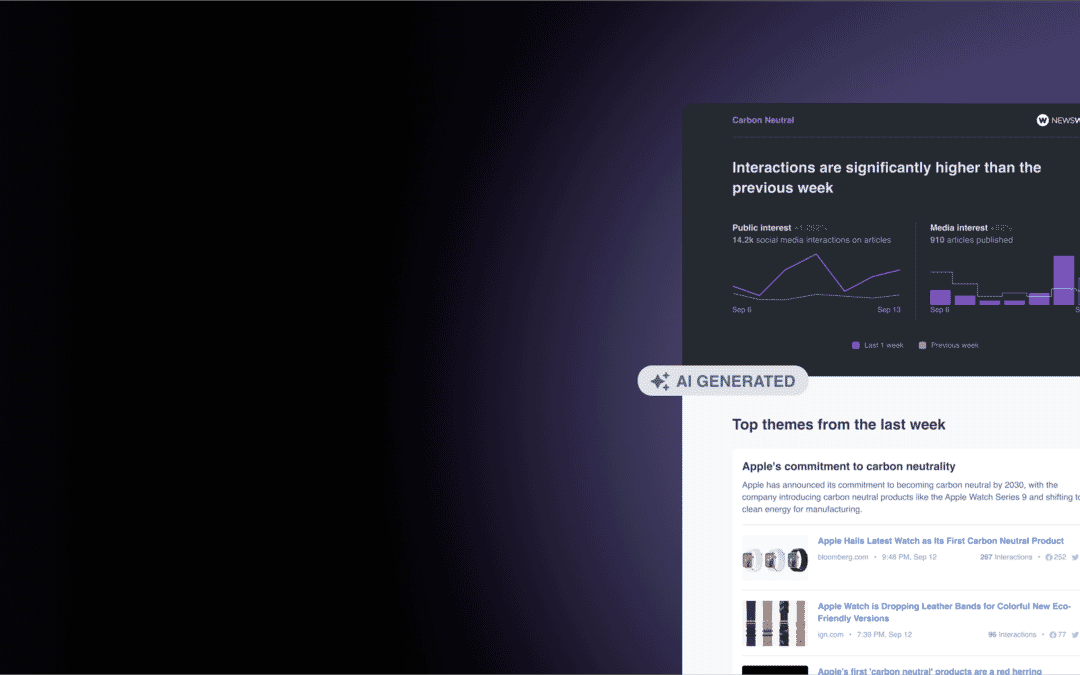

As seen in the above graphic, NewsGuard rated the website as red so that readers would know to treat any content the website produces with caution. This allows users to approach a story with greater context than they might otherwise have.

“The reason we do it this way is we do something that we call prebunking,” says Brandt. “Rather than debunking and waiting for a fact check to be published or waiting for an article to be evaluated by a team of fact checkers, we provide people with context about the source immediately. The first time they come across any new article from that source, they’re immediately warned about the reliability.”

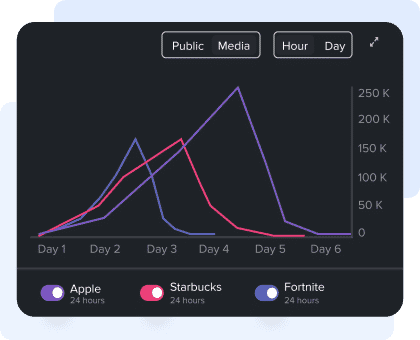

In order to make this process easier, Brandt and her team use NewsWhip. “What we’re doing is really limited in that it’s human driven — we can’t read every website out there, so we have to prioritize,” she says. “We rate all of the thousands of websites that account for at least 95% of engagement with news. We’re reading all of the websites that are getting the most engagement on Facebook, Twitter, and other social platforms. That’s important because that way we’re able to address the majority of the content that people are actually seeing and being impacted and potentially misled by.”

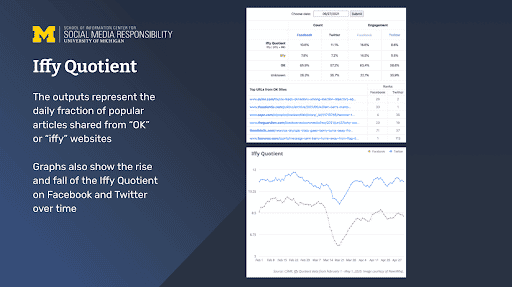

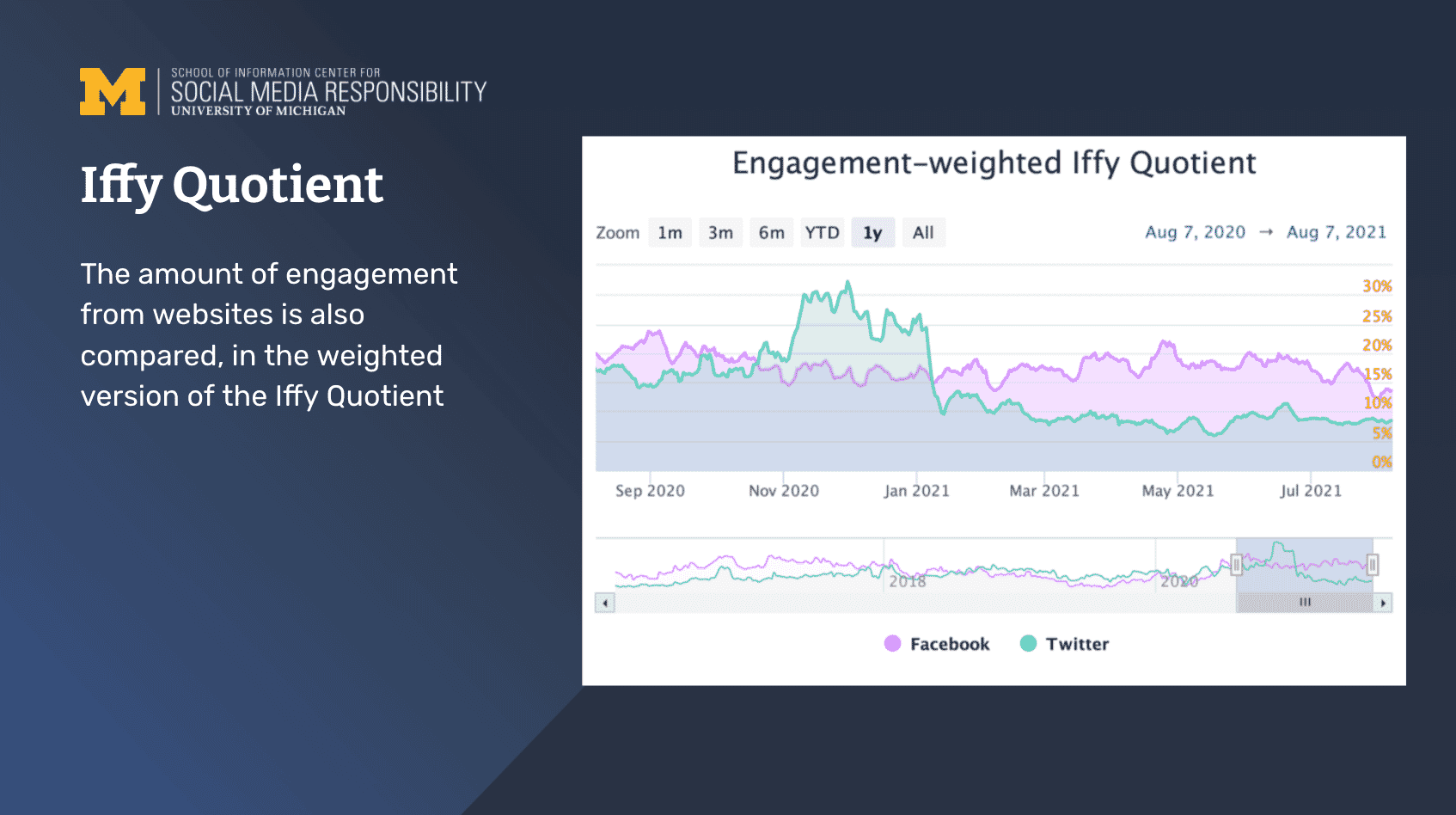

Meanwhile, researchers from the University of Michigan have developed a tool called the “Iffy Quotient.”

“We’ve combined data from NewsWhip and NewsGuard to produce this Iffy Quotient,” says Dr. Resnick. “On each day, we take from NewsWhip the 5,000 most engaged with URLs on Facebook and on Twitter. Of those, we see what percentage of them are coming from NewsGuard red sites. Those are the ones that we’re calling iffy.”

The Iffy Quotient doesn’t evaluate the truth of each particular URL as it gets published. Some of them may be true, and that’s why it’s called iffy instead of false.

This is mostly used at their Center for Social Media Responsibility, which is trying to help social media platforms meet their public responsibilities. One of their main responsibilities is creating accountability metrics where they try to see over time, not just whether these platforms sometimes have some level of misinformation, but how often and how much engagement does it get, and are they getting better at it over time.

Noting changes in the graphs of the Iffy Quotient, Dr. Resnick spoke on some of the interesting trends observed from this last year. The team found there was a flight to quality information sources, so less iffy content being shared at the beginning of the pandemic, but there was an increase in the Iffy Quotient during the 2020 election.

The future of misinformation

If we look at sources like the latest Edelman Trust Barometer, people around the world don’t trust any major institutions. Businesses have become the most trusted institution, more so than the media and government, especially in the US. So how can we rebuild institutional trust?

Declining trust in institutions of all kinds has been going on for 30 or 40 years. Dr. Resnick explains that we as a society haven’t spent enough time thinking about what signals people can use to decide who is trustworthy.

In the end, reputation is key. “We’re going to have people saying, “I’m going to follow those that have a positive reputation and anybody who’s new, I’m going to have to be a little suspicious about until they’ve proven themselves,” which is different from how we tend to think of things as “until you’ve done something wrong, I’m going to assume you’re good,” says Dr. Resnick. “It’s reasonable that you would walk down the street that way, but it’s not reasonable that you’re going to wander around the internet that way when people are deliberately trying to exploit that, so I think it’s going to depend on positive reputations of entities that build up trust over time.”

Brandt agrees, and credits the politicization of these topics as the issue when it comes to rebuilding trust. “We can’t even have productive cross-aisle conversations if there’s not even agreement over what the basic facts are. When you see things like health matters politicized, it’s just a complete breakdown. I don’t know how we return to disagreements over approaches rather than facts, and that’s one thing that needs to come back.”

Why brands should care about misinformation

We often see that NGOs and the media should care about misinformation, but what about brands themselves? They’re just as involved in the process as others, and it comes down to advertisements.

NewsGuard found that many of the major misinformation sources that get a lot of engagement online are able to do so because they’re running programmatic advertising. Every time their articles get clicked on, they increase their revenue. NewsGuard found that more than 4,000 brands have inadvertently been running programmatic ads on misinformation websites, publishing misleading facts about everything from COVID to the 2020 US elections.

“The issue is that existing brand safety solutions that brands think they’re using aren’t properly shielding brands from this,” says Brandt. “It doesn’t only produce reputation risk programs, but it also means they’re contributing to this toxic online ecosystem inadvertently.”

Dr. Resnick agrees that advertisers are going to be the key player in cleaning up the misinformation space. He explained that “iffy” sites are getting ads from major brands, but that major brands wouldn’t want that if they had more advanced controls to block it.

Misinformation will continue to persist. By staying informed, and using tools like NewsGuard’s rating system, NewsWhip’s media intelligence, or the Iffy Quotient, both brands and the public will have a much easier time navigating the true facts.

If you’d like to learn more about misinformation monitoring, check out NewsWhip’s product suite here.